Silence, Sorrow, and Separation: Birth Mothers and Birth Searching in Children’s Literature

Where is home? Is it with the families that raised us? For many adoptees of color, loving our parents or siblings does not prevent us from feeling that we are missing a piece of ourselves. As young children, we search in vain for someone who resembles us, who can show us our connectedness to the rest of humanity… All adoptees are faced with the dilemma of whether to search for our birthmothers and the possibility of another rejection if we do find them… Intensely emotional and unpredictable, our reunion stories have become fodder for public consumption, sparking curiosity and voyeurism. (Introduction to Outsiders Within, 2006, p. 11)

Being adopted is a passive situation. Looking for birth parents, by contrast, is a choice. (Marianne Novy, Reading Adoption, 2005, p. 2)

[ An important disclaimer: I am not an adopted Korean nor am I the birth mother of an adopted person. I am the daughter of immigrant Koreans. About 15 years ago, I began studying representations of Korean adoption in children’s literature for my doctoral dissertation. In 2009, I moved to Minnesota, the epicenter of transracial Korean adoption (Park Nelson, 2018), where I met my husband, who is an adopted Korean. As an Adoption Studies scholar, I prioritize listening to the voices of adopted persons and drawing from critical adoption studies.

My goal with this post is to amplify the voices of adopted persons and their birth mothers, the two silenced members of the adoption constellation. ]

“The fact that I lost my son permeates my being.”

In 2012, I saw children’s book author Lois Lowry during her book tour for Son, the final book in The Giver quartet. Lowry spoke about how the death of her son during a flight accident was one of her inspirations for writing the book. She told The New York Times, “The fact that I lost my son permeates my being.” The NYTimes continues, “And that loss permeates ‘Son’ as well. It’s a book of longing in the guise of an adventure. Children will love it. It will break their parents’ hearts.”

That evening, I thought, “Son is a birth search story.” I asked Lowry if she had done research on adoption, birth mothers, and birth searching for this book, and she paused and replied that she hadn’t thought of Son as an adoption narrative. I knew then that someday I wanted to write about it. Though I have been researching representations of Korean adoption in youth literature since the early 2000s, I have not seen Korean birth mothers depicted with much depth and care (Somebody’s Daughter by Marie Myung-Ok Lee is generally advertised as an adult novel). This may be because American children’s books depicting Korean transracial adoption are primarily written by white women, and particularly by white adoptive mothers, who fail to “imagine” (Thomas, The Dark Fantastic) the experiences of Korean birth mothers.

In 2019, I presented a version of this essay at the biennial congress of the International Research Society for Children’s Literature (Stockholm). The theme of the congress was “Silence and Silencing in Children’s Literature” and my presentation was part of a panel titled, “Shattering Silences and Stereotypes in Transnational Adoption Narratives,” along with adoptees Shannon Gibney and Tobias Hübinette.

Birth Mothers and Adoption Discourse in the United States and Republic of Korea

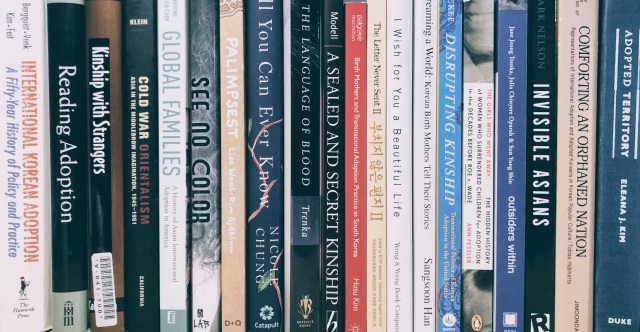

The U.S. and Korea dominate in terms of both adoption practice and critical adoption studies (see Kim Park Nelson’s Invisible Asians, 2016, and Kimberly Mckee’s Disrupting Kinship, 2019). Korean transnational adoption began in the 1950s during the Korean War and escalated through the 1980s, when thousands of children were sent for overseas adoption. More than 200,000 Koreans have been adopted to countries outside of Korea, with about half going to the United States (see Tobias Hübinette for a history through 2004; see also Kim Park Nelson; Eleana Kim; Kimberly McKee; Elizabeth Raleigh).

Birth mothers are often rendered invisible members of the adoption constellation. Specifically, many Korean birth mothers suffer in silence. In Virtual Mothering: Birth Mothers and Transnational Adoption Practice in South Korea (2016), Hosu Kim writes about how poverty, being widowed, abuse, rape, and the stigma of single motherhood lead many Korean women to relinquish their children; fathers are rarely held accountable. As American demand for adoptable children increased, Korea sent away thousands of children, turning a system that originally found families for children into one that found children for families. Social workers admitted to going to poor neighborhoods in search of single mothers and pressuring them to place their children for adoption. Consequently, for a while now, 95% of the children adopted out of Korea were born to single mothers; their “social death” (Orlando Patterson and Jodi Kim, cited in Hosu Kim, 2016, p. 9) is what renders children available for adoption. They are, as Lois Lowry writes, a “vessel.”

We have most commonly seen Korean birth mothers on Korean television shows as they are being reunited with their children. But these scripted reunions hardly allow birth mothers to speak for themselves (Kim, 2016). By individuating birth mothers and ignoring the larger multi-decade, multi-million dollar “transnational adoption industrial complex” (McKee, 2019), Kim writes that “the search and reunion narrative enforces a normative motherhood in which birth mothers remain disconnected from South Korea’s long history of transnational adoption and trapped in a sense of shame and guilt for their failure of mothering, and thus further discourages them from speaking about their experiences” (2018, p. 323).

Birth mothers in the United States are also silenced. Ann Fessler says in The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Their Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade (2006): “… it is remarkable that so little is known about these mothers’ experiences even now, decades later. This silence has also kept many of these women from learning about one another and understanding that their feelings of grief and loss were normal…” (p. 12). Fessler shares the stories of women who were, in the words of one woman, “told they must surrender their child, keep their secret, move on and forget” (p. 9). The women, who were mostly teenagers at the time of their pregnancies, were meant to just, well, forget and be forgotten. Fessler continues, “… none of the mothers I interviewed was able to forget. Rather, they describe the surrender of their child as the most significant and defining event of their lives” (p. 12). One birth mother said, “A lot of us are still suffering in silence” (p. 52).

Many children’s books are silent on the topic of birth parents and birth searching. However, we must discuss birth parents’ roles in adopted people’s lives, partly out of justice for the birth parents who are the “primary actor[s]” in adoption (Modell, Kinship with Strangers, 1994, p. 63), and partly out of the need to counteract the dominant images and discourse that diminish their roles or write them out of adoption stories (Kim 2007; Modell 1994, pp. 12, 61-90; Novy 2005, p. 13; Oparah, Shin and Trenka 2006, pp. 3, 12-13; Pertman 2000, pp. 8, 11, 148-150). In youth literature, if Korean birth mothers are depicted at all, they are made into passive objects whose primary act is to give birth and then give away a child, or they are discursively written out of the narrative. They are likely to be deceased, drawing on both the social and actual death Hosu Kim references.

Therefore, I am fascinated by the depth of character and compassion accorded to both the searching child and his grieving birth mother in Son.

Birth Mothers and Birth Searching in Son

Son (2012) is the fourth book in The Giver quartet. In The Giver (1993), a child named Gabriel is born to a birth mother in a tightly controlled community. When the protagonist Jonas realizes that Gabriel will be “released,” a euphemism for being euthanized, for “failing” to develop properly, he takes him and runs away to Elsewhere. Son takes place when Gabriel is a teenager. The story is mostly about Claire, the woman who gave birth to Gabriel in The Giver. In Son, readers witness Gabriel’s conception, birth, separation, and search from Claire’s perspective.

I map Claire’s emotions and experiences to birth mothers’ testimonies in Fessler’s and Kim’s research. First, birth mothers are underprepared regarding pregnancy, birth, and relinquishment. Claire “had not known, until she both experienced and observed it, that human females swelled and grew and reproduced. No one had told her what ‘birth’ meant” (p. 27). Later, in a conversation with a fellow birth mother who had already given birth, Claire learns for the first time that the process might be “uncomfortable.” Fessler reports that “Most of the women [she] talked to had been wholly uninformed about sex and pregnancy prevention” (p. 45). Later, Fessler also writes, “These women were even less prepared and were completely taken aback by the intense feelings of love they had for their child at birth” (p. 180). Claire, who by accident is no longer taking the emotions-numbing pills distributed to each member of the community, experiences these feelings.

Immediately after Gabriel was born and taken away, Claire thought, “… she missed it. She was suffused with a desperate feeling of loss” (p. 11), echoing Fessler’s observations that “moving on and forgetting was impossible. The full emotional weight of the surrender affected some immediately” (p. 187). Claire goes on: “… ever since the day of the birth, she felt a yearning constantly, desperately, to fill the emptiness inside her. She wanted her child” (p. 59). One birth mother in Fessler’s book shared, “The first few weeks at home, I cried all the time… I cried all night, but I didn’t let anybody hear me…” (p. 200). Hosu Kim likewise observes the “feelings of shame, guilt, lowered self esteem, and self-loathing as well as of depression, an emptiness…” (p. 204) expressed by Korean birth mothers.

Over time, birth mothers do not forget their relinquished children. Using the present tense, Hosu Kim writes about the “emotional devastation [the Korean birth mothers] are suffering over their lost child” (p. 169) and the “prolonged sense of unresolved grief” (p. 204) reflected in their online posts. Fessler reports that one birth mother said, “Even if my mind didn’t remember it, my body remembered. This really lives in your body” (p. 210). Similarly, when someone says to Claire, “You love your boy, though,” and even though it’s been years, she responds: “I loved my boy. I still do.” (p. 228). Again, the present tense indicates ongoing grief.

Finally, readers learn that while Claire has been desperate to find her son, Gabriel has also been desperate to learn about his past. He asks Jonas questions such as, “What happened to the birthmothers? What happened to my birthmother” (p. 274) “Didn’t she want me?” “I’m going to find out” (p. 274). Laurel Kendall notes that “adoption self-help literature tells us that all adopted children think about their birth parents and some even construct powerful fantasies around them” (2005, p. 163). In the early 2000s, the Korean adoption agencies reported that about 2-3% of searching adoptees had reunified with their birth families. I can’t imagine the number is much higher now, but it may be skewed because while we hear about “successful” reunions, we hardly hear about the searches that do not lead to a reunion (see Found in Korea by Nam Holtz). We also hardly hear about the difficulty of reunions or how birth searches often reveal corruption in the adoption process (see Palimpsest by Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom; First Person Plural and In the Matter of Cha Jung Hee by Deann Borshay Liem). Gabriel’s desperation to find his birth mother resonates with research I’ve conducted regarding Korean birth searches, especially in reading the first person accounts of Korean adoptees in memoirs, short story collections, online, and in documentaries, as well as the stories I’ve heard and observed first hand from Korean adoptee friends and colleagues.

#FlipTheScript: Centering Birth Mothers and Adopted Persons

Birth searching, grief, and loss on the part of birth mothers and their children seem fully realized in this novel written by and possibly featuring white people. It shows the reader how much birth mothers suffer as a result of having children taken from them. Claire is silenced, but she cannot suppress her sorrow in being separated from her baby. Readers see her grief, and we are encouraged to empathize and hope that Claire and Gabriel will be successful in their searches.

In contrast, the actual sorrows suffered by birth mothers—whether Korean or American—who have their children taken from them or who are otherwise separated from their children, have their stories told in venues other than in children’s literature, and even within those venues, they are underrepresented. Adoptees are also severely underrepresented as authors in children’s literature; most Korean adoption narratives are written by white women, with nearly half by white adoptive mothers (Park, 2009). Similarly, adoptee Liz Latty observes that “The vast majority of children’s books about adoption are written by adoptive parents” that lead to a “dominant narrative of adoption [that] is one of unquestionable good, a one-time event, and win-win for everyone involved” (“Dismantling Whitewashing & Saviorism In Adoption Kidlit,” Books for Littles.) On Lost Daughters, adoptees write, “Whenever education is taking place about an issue or community, all voices of that community must be included. The world needs to hear adoptee voices included in the dialogue about adoption.” It is crucial that we #FlipTheScript and center the voices of adopted persons and birth mothers.

In 2019, I heard Celeste Ng talk about her 2017 novel, Little Fires Everywhere (now streaming on Hulu). As I did during Lois Lowry’s event, I raised my hand during the Q&A. First, I thanked Ng for writing the character of the birth mother in a way that included her back story, made her more human, and gave her an ending that so few birth mothers get in real life and in fiction. I then asked her what research she did on birth mothers, adoption, etc., before writing the book. Ng went into detail about her research, citing specific court cases where birth and adoptive parents wrestled for the right to parent a particular child. She, too, wrote the birth mother character in a way that encouraged the readers’ sympathy. Lisa Ko’s The Leavers (2016) similarly depicts an adoption, birth mother, and birth search; Lisa Ko is not an adopted person and writes about her inspiration for the story here.

Fessler observes that the birth mothers’ “grief has been exacerbated… because they were not permitted to talk about or properly grieve their loss” (p. 208). Hosu Kim says, “While information about the existence and experiences of birth mothers is seriously limited in the South Korean discourse on transnational adoption, the experiences of birth mothers is even less acknowledged in the adoption discourse in North America and Western Europe… birth mothers have remained treated, at best, as a symbol of a remote, unknown, and unfortunate past, and at worst, are assumed to be literally dead” (2016, p. 4). Kim also notes that when birth mothers meet adopted Koreans (not their biological children), “In accounting the circumstances leading to putting children up for adoption, and in their experiences with adoptees, the birth mothers are transformed into living documents. By sharing their life stories, at times too painful to remember, birth mothers breathe life into information that might otherwise remain unavailable or abstract to adoptees” (2018, p. 331). Shannon Bae extends the work Kim began, amplifying the “radical imagination and solidarity” between Korean adoptees and birth mothers that point to a present and future where neither of their voices are silenced (2018).

Therefore, I conclude with a call to break the silences that persist around adoption discourse, and particularly around birth mothers’ rights, grief, and loss. Their full humanity should not be relegated to fiction, but fiction may very well help us to have more compassion for birth mothers.

I deliberately chose Mother’s Day for my #31DaysIBPOC post. Today, May 10th, is also Single Parent Families’ Day in Korea (Bae). On this day and with this post, I honor the women who have lost children to adoption. Their stories matter.

Works Cited

Bae, Shannon. (2018). “Radical Imagination and the Solidarity Movement Between Transnational Korean Adoptees and Unwed Mothers in South Korea.” Adoption & Culture 6(2).

Fessler, Ann. (2006). The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade. Penguin Books.

(2014). “#FlipTheScript.” Lost Daughters website.

Kendall, Laurel. (2005). “Birth Mothers and Imaginary Lives” in Cultures of Transnational Adoption, ed. Toby Alice Volkman, 162-181. Duke University Press.

Kim, Hosu. (2007). “Mothers Without Mothering: Birth Mothers from Korea Since the Korean War” in International Korean Adoption: A Fifty-year History of Policy and Practice, eds. Kathleen Ja Sook Bergquist, Elizabeth M. Vonk, Dong Soo Kim and Marvin D. Feit, 131-153. The Haworth Press.

Kim, Hosu. (2016). Birth Mothers and Transnational Adoption Practice in South Korea. Palgrave.

Kim, Hosu. (2018). “Reparation Acts: Korean Birth Mothers Travel the Road from Reunion to Redress.” Adoption & Culture 6(2).

Hübinette, Tobias. (2004). “Korean Adoption History” in Guide to Korea for Overseas Adopted Koreans, ed. Eleana Kim. Overseas Koreans Foundation.

Ko, Lisa. (2017). The Leavers. Algonquin Books.

Latty, Liz. (2019). “Dismantling Whitewashing & Saviorism In Adoption Kidlit.” Books for Littles.

Lowry, Lois. (1993). The Giver. Houghton Mifflin.

Lowry, Lois. (2012). Son. HMH Books for Young Readers.

McKee, Kimberly. (2019). Disrupting Kinship: Transnational Politics of Korean Adoption in the United States. University of Illinois Press.

Modell, Judith S. (1994). Kinship with Strangers: Adoption and Interpretations of Kinship in American Culture. University of California Press.

(2012 Oct 3). “The Children’s Author Who Actually Listens to Children.” New York Times Company.

Ng, Celeste. (2017). Little Fires Everywhere. Penguin Books.

Novy, Marianne. (2005). Reading Adoption: Family and Difference in Fiction and Drama. University of Michigan Press.

Oparah, Julia Chinyere, Sun Yung Shin, and Jane Jeong Trenka. (2006). “Introduction” in Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption, eds. Jane Jeong Trenka, Julia Chinyere Oparah and Sun Yung Shin, 1-15. South End Press.

Park, Sarah Young. (2009). Representations of Transracial Korean Adoption in Children’s Literature. University of Illinois.

Park Nelson, Kim. (2016). Invisible Asians: Korean American Adoptees, Asian American Experiences, and Racial Exceptionalism. Rutgers University Press.

Park Nelson, Kim. (2018). “Korean Transracial Adoption in Minnesota.” MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society.

Pertman, Adam. (2000). Adoption Nation: How the Adoption Revolution is Transforming America. Basic Books.

Sjöblom, Lisa Wool-rim. (2019). Palimpsest: Documents from a Korean Adoption. Drawn & Quarterly.

Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth. (2019). The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games. New York University Press.

Notes

Special thanks to Dr. Betina Hsieh, Erica Kanesaka Kalnay, and Dr. Kimberly McKee for providing feedback on this post.

[ This blog post is part of the #31DaysIBPOC Blog Challenge, a month-long movement to feature the voices of Indigenous and teachers of color as writers and scholars. Please CLICK HERE to read yesterday’s blog post by Laura M. Jiménez (and be sure to check out the link at the end of each post to catch up on the rest of the blog circle). ]